Playing a World Series in “unprecedented times”

2020 still has a few months left to go —*sigh*—but it will undoubtably go down in the books as one of the most consequential years in modern history. To paraphrase all those marketing emails, we truly are living in “unprecedented times.”

In keeping with that theme, Major League Baseball’s 2020 postseason is about to be contested at a series of neutral sites, culminating with the World Series, which is scheduled to be played entirely at the Texas Rangers’ new $1.1 billion Globe Life Field. This will mark the fourth time in MLB history that the entirety of the Fall Classic will have taken place in a single stadium, staring with the 1921 and 1922 matchups between the New York Giants and Yankees, who shared the Polo Grounds. The most recent World Series to have taken place at a lone venue was the 1944 Series, which was played at St. Louis’ Sportsman’s Park.

That “Streetcar Series” between St. Louis’ Browns and Cardinals took place during another year of great consequence. Set against the backdrop of World War II, MLB’s talent pool was seriously depleted, the perfect moment for the consistently moribund Browns to capture their first (and only) American League pennant. The National League champion Cardinals, on the other hand, were a perennial juggernaut, en route to their third consecutive World Series appearance. The underdog Brownies may have been “the people’s choice,” but the Cards were a force to be reckoned with, jumping out to a big lead during the regular season and never looking back. (At one point they ran up a gaudy 89-29 record.) They finished up with 105 victories and came into the Fall Classic as heavy favorites. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch termed the Cardinals “(t)he only club in either league to be rated as approximating pre-war strength.”

Sportsman's Park, located at Dodier Street and Grand Avenue in north St. Louis, played host to both clubs from July 1920 until the Browns moved to Baltimore following the conclusion of the 1953 season. The Browns owned the ballpark, which was located on a site that first hosted baseball games in 1866. The Cardinals, fronted by Anheuser Busch scion August Busch, purchased the stadium in 1953, with the intent to rename it “Budweiser Stadium.” The Browns, a franchise in perpetual financial disarray, signed a five year lease—they would play but one season as tenants before relocating to Maryland and becoming the Baltimore Orioles.

Even with the entire Series being contested in one place, wartime travel restrictions and gas rationing were a theme. The Sporting News ran a series of license plate photos (with numbers and letters left unobscured) from states that included Georgia, Indiana, Oklahoma, and Florida, noting “(d)espite gasoline rationing and…restrictions against the sale of tickets to persons outside of the St. Louis area, a number of out-of-state-licenses were noted on cars parked in lots and streets around Sportsman’s Park…” The Post-Dispatch reported “(a) staff of investigators was busy checking cars from distant points in Missouri, Illinois, and from other states.”

There was also a national housing shortage in progress, which forced some creative approaches to living arrangements. Browns’ manager Luke Sewell and his Cardinals counterpart, Billy Southworth, along with their families, shared an apartment during the regular season. This situation worked out well—when the Cards were in town, the Browns were on the road. The Sewells temporarily vacated in favor of the Southworths and vice versa, on and off, all season long. Any leftover groceries became property of the incoming family and the two skippers shared a clothes closet. Something had to give with both clubs playing at home during the World Series, however, and Southworth vacated the apartment in favor of a hotel room. Similarly, the Browns and Cardinals rotated dugouts during the fall Classic, with the NL champs being designated as the home team for Games 1, 2, and 6 and the AL champions gaining home status for Games 3, 4, and 5. Tickets for the Series shared a common design as well, with the Cardinals’ home game stubs printed in red and blue and the Browns in brown and red.

The 1944 World Series was the first in which every game was played west of the Mississippi River. It was also one of the last that was exclusively white—Jackie Robinson and teammate Dan Bankhead broke the World Series color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Like 2020, 1944 featured a US Presidential election. Missouri Senator Harry S Truman, the Democratic vice-presidential candidate, attended Game 3.

Oddsmakers tapped the Cardinals as 9-5 favorites, but the Browns put up a good fight. On October 4 they took Game 1 of the Series with a 2-1 victory. The Cardinals bounced back in Game 2 with an 11-inning walkoff 3-2 win. Game 3 went to the Brownies, 6-2, but the Cards won the next three, wrapping up the Series up with a 3-1 Game 6 victory.

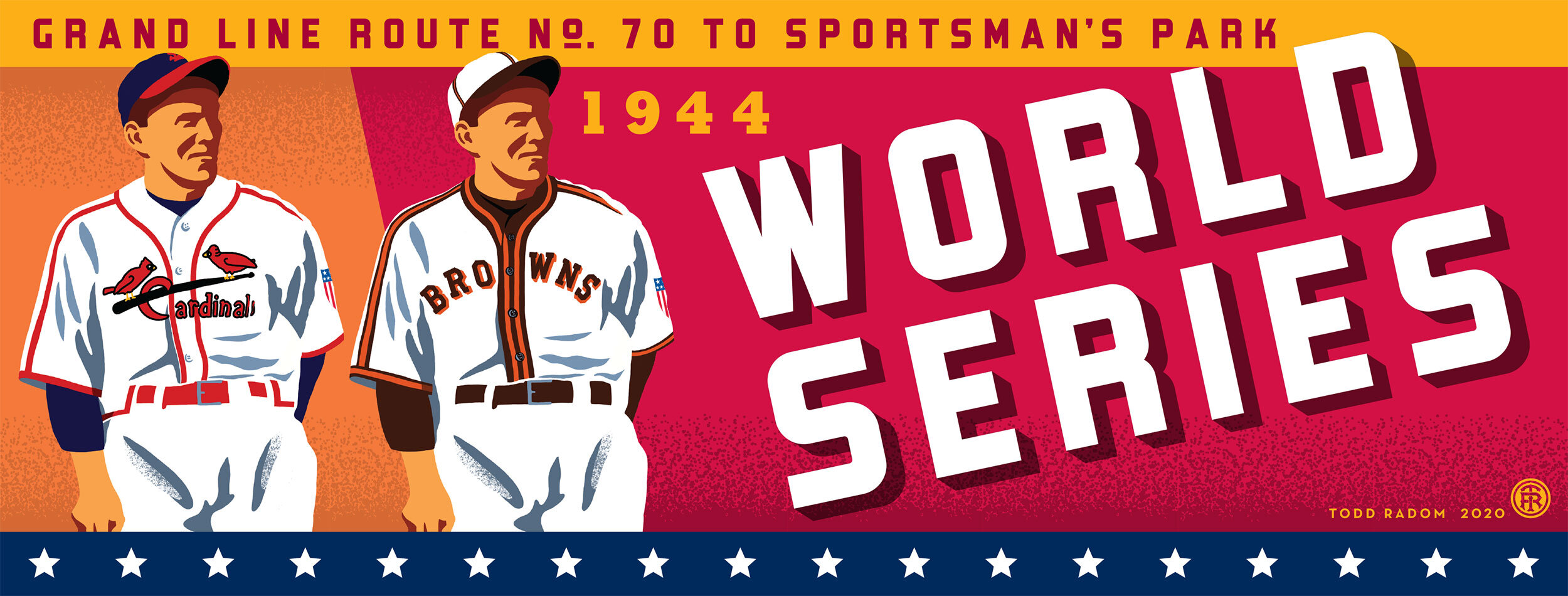

In hindsight, the optics of this Fall Classic make it a sartorial classic for the ages. Both teams were outfitted in fresh uniforms, supplied by St. Louis’ own Rawlings. The Cardinals’ zippered regular season jerseys were replaced by buttoned togs. Both clubs wore identical sleeve patches—a simple shield containing 13 white stars, set against a blue background, accompanied by thirteen red and white stripes.

Each club wore jerseys with bold, expressive trim cascading down the shoulders and across the sleeves. The Cardinals’ uniforms were trimmed in red (they wore similarly decorated belt loops as well,) and the Browns’ front trim consisted of fancy brown and orange satin plackets. The Brownies’ jerseys were topped off with brown block lettering, backed up by a bold orange drop shadow. The Cardinals’ jerseys then, as now, were stylishly decorated with what was officially described as an “insignia of two cardinal birds resting on a black bat with a narrow outline of royal blue and ‘Cardinals’ in red with blue outline across shirt front. The details have evolved since then, but the effect remains unchanged. Interestingly, the Browns’ caps featured no logo at all—just a series of six brown and orange stripes that delineated the panels of the headwear (this was a signature Brownie thing; it was utilized as the core design feature for the Browns’ 1948 All-Star Game press pin.) 1944 marks the most recent time that a World Series club wore caps with no insignia.